The power of unbiased recursive partitioning

Citation

Schlosser L, Hothorn T, Zeileis A (2019). “The Power of Unbiased Recursive Partitioning: A Unifying View of CTree, MOB, and GUIDE”, arXiv:1906.10179, arXiv.org E-Print Archive. https://arXiv.org/abs/1906.10179

Abstract

A core step of every algorithm for learning regression trees is the selection of the best splitting variable from the available covariates and the corresponding split point. Early tree algorithms (e.g., AID, CART) employed greedy search strategies, directly comparing all possible split points in all available covariates. However, subsequent research showed that this is biased towards selecting covariates with more potential split points. Therefore, unbiased recursive partitioning algorithms have been suggested (e.g., QUEST, GUIDE, CTree, MOB) that first select the covariate based on statistical inference using p-values that are adjusted for the possible split points. In a second step a split point optimizing some objective function is selected in the chosen split variable. However, different unbiased tree algorithms obtain these p-values from different inference frameworks and their relative advantages or disadvantages are not well understood, yet. Therefore, three different popular approaches are considered here: classical categorical association tests (as in GUIDE), conditional inference (as in CTree), and parameter instability tests (as in MOB). First, these are embedded into a common inference framework encompassing parametric model trees, in particular linear model trees. Second, it is assessed how different building blocks from this common framework affect the power of the algorithms to select the appropriate covariates for splitting: observation-wise goodness-of-fit measure (residuals vs. model scores), dichotomization of residuals/scores at zero, and binning of possible split variables. This shows that specifically the goodness-of-fit measure is crucial for the power of the procedures, with model scores without dichotomization performing much better in many scenarios.

Software

CRAN package: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=partykit

Development version with some extensions enabled: partykit_1.2-4.2.tar.gz

Replication materials: simulation.zip

Main results

The manuscript compares three so-called unbiased recursive partitioning algorithms that employ statistical inference to adjust for the number of possible splits in a split variable: GUIDE (Loh 2002), CTree (Hothorn et al. 2006), MOB (Zeileis et al. 2008).

First, it is pointed out what the similarities and the differences in the algorithms are, specifically with respect to the split variable selection through statistical tests. Second, the power of these tests is studied for a “stump”, i.e., a single split only. Third, the capability of the entire algorithm (including a pruning strategy) to recover the correct partition in a “tree” with two splits is investigated.

In all cases, the three algorithms are employed to learn model-based trees where in each leaf of the tree a linear regression model is fitted with intercept β0 and slope β1. The simulations then vary whether only the intercept β0 or the slope β1 or both differ in the data.

Building blocks of the algorithms and their test statistics

All three algorithms proceed by first fitting the model (here: linear regression by OLS) in a given subgroup (or node) of the tree. Then they extract some kind of goodness-of-fit measure (either residuals or full model scores) and test whether this measure is associated with any of the split variables. The variable with the highest association (i.e., lowest p-value) is employed for splitting and then the procedure is repeated recursively in the resulting subgroups.

For “pruning” the tree to the right size one can either first grow a larger tree and then prune those splits that are not relevant enough (post-pruning). Or the algorithm can stop splitting when the association test is not significant anymore (pre-pruning).

The default combinations of fitted model type, test type, and pruning strategy for the three algorithms are given in the following table.

| Algorithm | Fit | Test | Pruning |

|---|---|---|---|

| CTree | Non-parametric | Conditional inference | Pre |

| MOB | Parametric | Score-based fluctuation | Pre (or post with AIC/BIC) |

| GUIDE | Parametric | Residual-based chi-squared | Post (cost-complexity pruning) |

Thus, the main difference is the testing strategy but also the pruning is relevant. While at first sight, the tests come from very different motivations, they are actually not that different. When assessing the association with the split variable the following three properties are most relevant:

- Goodness-of-fit measure: Either the full model scores which are here bivariate with one component for the intercept (= residuals) and one component for the slope. Alternatively, only the residuals are used.

- Dichotomization of residuals/scores: Are the numeric values used for the residuals/scores? Or are they dichotomized at zero?

- Categorization of split variables: Are the numeric values used for the split variables? Or are they binned at the quartiles?

An overview of the corresponding settings for the three algorithms is given in the following table. Additionally, the tests differ somewhat in how they aggregate across the possible splits considered. Either in a sum-of-squares statistic or a maximally-selected statistic.

| Algorithm | Scores | Dichotomization | Categorization | Statistic |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CTree | Model scores | – | – | Sum of squares |

| MOB | Model scores | – | – | Maximally selected |

| GUIDE | Residuals | X | X | Sum of squares |

Subsequently, these algorithms are compared in two simulation studies. More details and more simulation studies can be found in the manuscript. In addition to the three default algorithms, a modified GUIDE algorithm using model scores instead of residuals (GUIDE+scores) is considered.

Properties of the tests for a single split (or stump)

Clearly, the different choices made in the construction influence the inference properties of the significance tests. Hence, in a first step we investigate the power properties of the tests when there is only one split in one of the split variables (among further noise variables). The split can pertain either to the intercept β0 only or the slope β1 only or both.

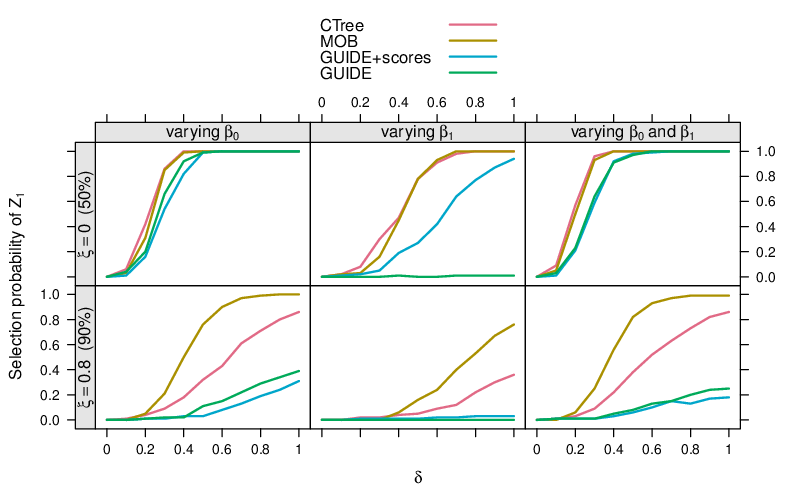

The plot below shows the probability of selection the true split variable (Z1) with the minimal p-value against the magnitude of the difference in the regression coefficients (δ). For a split in the middle of the data (50%) pertaining only to the intercept β0 (top left panel) all tests perform almost equivalently. However, if the split only affects the slope β1 (middle column) it is much better to use score-based tests rather than residual-based tests (as in GUIDE) which cannot pick up changes that do not affect the conditional mean. Moreover, if the split occurs not in the middle (50% quantile, top row) but in the tails (90% quantile, bottom row) it is better to use a maximally-selected statistic (as in MOB) rather than a sum-of-squares statistic.

Properties of the algorithms for a tree with two splits

One could argue that the power properties of the tests may be crucial when pre-pruning (based on statistical significance) is used. However, when combined with cost-complexity post-pruning it may not be so important to have particularly high power. As long as the power for the true split variables is higher than for the noise variables, it might be sufficient to select the correct split variable.

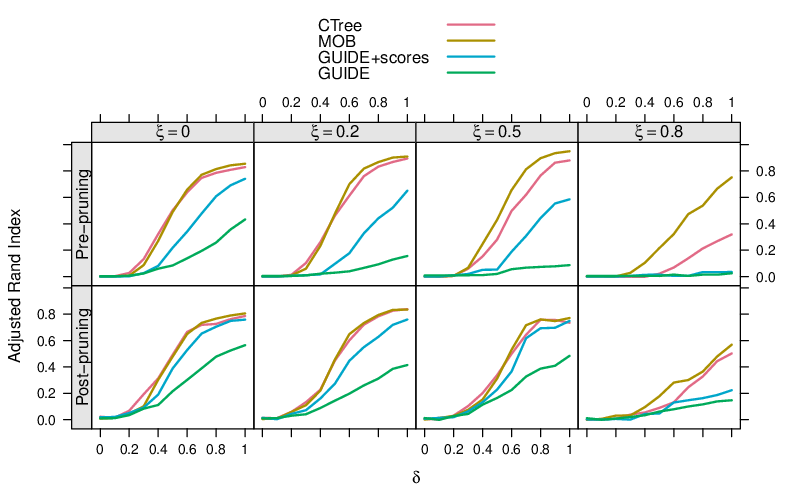

This is assessed in a simulation for a tree with two splits, both depending on differences of magnitude δ in the two regression coefficients, respectively. The adjusted Rand index is used to assess how well the partition found by the tree conforms with the true partition. The columns of the display below are for splits that occur in the middle of the data vs. later in the sample (left to right).

And indeed it can be shown that post-pruning (bottom row) mitigates many of the power deficits of the testing strategies compared to significance-based pre-pruning (top row). However, it is still clearly better to use a score based test (as in CTree, MOB, and GUIDE+scores) than a residuals-based test (as in GUIDE). Also, pre-pruning may even lead to slightly better results than post-pruning when based on a powerful test.

Summary

Using several simulation setups we have shown that in many circumstances CTree, MOB, and GUIDE perform very similarly for recursive partitioning based on linear regression models. However, in some settings score-based clearly outperform residual-based tests (the latter may even lack power altogether). To some extent cross-complexity post-pruning can mitigate power deficits of the testing strategy but pre-pruning typically works as well as long as the significance test works well.

Furthermore, other simulations in the manuscript show that dichotomization of residuals/scores should be avoided as it reduces the power of the tests. Note that this is very easy to do in GUIDE: Instead of chi-squared tests one can simply use one-way ANOVA tests. Finally, in the appendix of the manuscript it is shown that maximally-selected statistics (as in MOB) work better for abrupt splits late in the sample while the sum-of-squares statistics (from CTree and GUIDE) work better for smooth(er) transitions.